A study led by scientists at the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the American National Cancer Institute (NCI) has revealed a way to promote the continued growth of tumors in the presence of tumor killer immune cells. The findings were recently published in the journal Science. A new method for enhancing antitumor immunotherapy is revealed.

Dead cancer cells release potassium ions, and in some tumors potassium levels are high. The team reports that elevated potassium causes T cells to maintain stem cell-like mass, or “stem cells”, which is closely related to their ability to eliminate cancer during immunotherapy. The results suggest that increasing T cell exposure to potassium-or mimicking the effect of high potassium-can make cancer immunotherapy more effective. “This study helps us better understand why cancer immunotherapy works. “Dr. Nicholas Restifo, a CCR researcher who led the team, said. “the study could also point the way to better and more lasting treatment response. ” Immunotherapy has had a significant effect on some cancer patients, eradicating refractory tumors and, in some cases, leading to complete remission of the disease.

“This study helps us better understand why cancer immunotherapy works. “Dr. Nicholas Restifo, a CCR researcher who led the team, said. “the study could also point the way to better and more lasting treatment response. ” Immunotherapy has had a significant effect on some cancer patients, eradicating refractory tumors and, in some cases, leading to complete remission of the disease.

But many patients’ tumors do not respond to immunotherapy, and researchers are trying to determine why. In addition, some immunotherapy methods, such as CAR-T cells and immune checkpoint inhibitors, are limited by the lifespan of T cells. Anti-cancer T cells in the tumor “run out” and die. As a result, researchers are exploring ways to help T cells used in immunotherapy survive longer and replicate and grow.

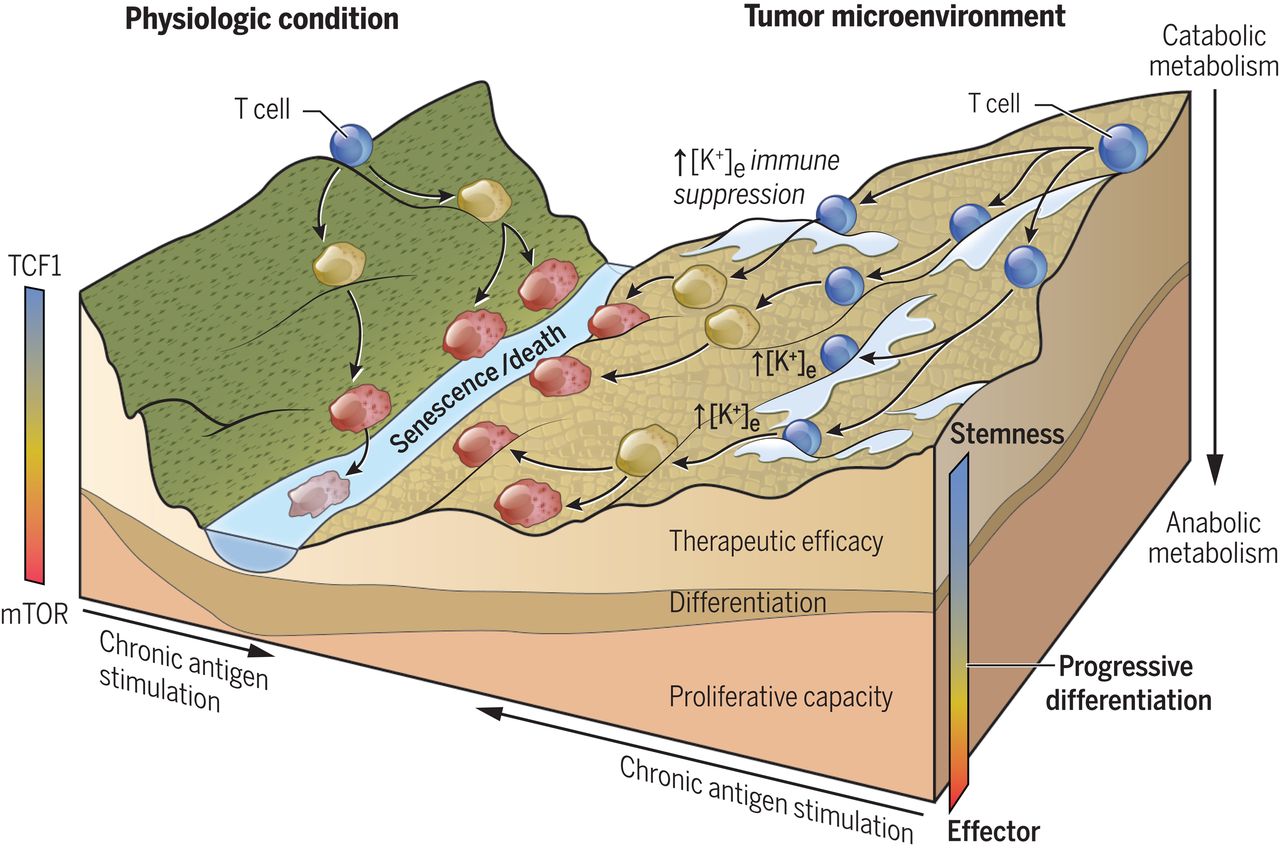

Dr. Restifo and his team have previously shown that high levels of potassium released into tumors by dying cancer cells prevent tumor-killing T cells from invading the tumor. In the new study, the researchers found that T cells growing under high potassium conditions also maintained the “dryness” of T cells. This means that stem cell-like T cells have the ability to replicate themselves in tumors, but they cannot mature into killer immune cells. By keeping T cells in this state, tumors can avoid attack and continue to grow. This may explain why there are T cells in the tumor, but the tumor cells can continue to grow.

However, when stem cell-like T cells are removed from the tumor, grow in large numbers in the laboratory, and then return to the patient, stem cell-like T cells can mature into killer cells that can attack the tumor. Dr. Restifo explained that the dryness of T cells-that is, their ability to renew themselves indefinitely and respond to stimuli to become anticancer cells may have contributed to the success of adoptive cell transfer therapy.

The researchers then explored the efficacy of using high potassium levels to preserve T cell stem cells for treatment. They found that T cells grown in high potassium environments were more effective in inhibiting primary and metastatic melanoma transplanted into mice. They also found that when exposed to high levels of potassium, both T cells isolated from patients’ tumors and genetically engineered cancer T cells had higher levels of markers associated with sustained growth and improved immunotherapy outcomes.

Finally, the team demonstrated that when they used specific drugs to simulate the effects of potassium on T cells in mice, they improved the ability of T cells to continue to grow and eliminate tumors. This means that the drug may be used to induce T cell dryness as a strategy to enhance immunotherapy for cancer. The next step, Dr. Restifo said, will be clinical trials, “using this knowledge for better treatment,” but he is also excited that the findings help us understand immunotherapy at the moment.

Reference

1. Vodnala, Suman Kumar, et al. “T cell stemness and dysfunction in tumors are triggered by a common mechanism.” Science 363.6434 (2019): eaau0135.